The Two Pillars

The first time that I ever got a good look at the inside of a Masonic lodge room was on the morning of my initiation. My grandfather took me into the lodge room at Carrollton (Kentucky) Lodge #134, and proceeded to inform me that everything in that room, down to the smallest item, was there for a very specific purpose, and that it all meant something—nothing was merely ornamental. My eyes were immediately drawn to the two large, free-standing pillars, which in that lodge were placed on either side of the entrance door. I asked him what they were and what they meant, and he replied, “Oh, you’ll find out more about them later.” That explanation did come a month later when I was passed to the degree of Fellowcraft.

However, in many ways the information communicated about these most important furnishings is not proportionate to their size and station. In Tennessee, for example, our attention is drawn only briefly to them in the second degree, and then the explanation is limited to their names, dimensions, and a description of their adornments. They are not mentioned again until they appear, almost as an afterthought, in the Royal Arch degree, in the list of those treasures that were taken to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar as the spoils of war. Little is given to explain the meaning or symbolism of the pillars themselves. In order to determine that, one must dig deeper into other sources, and that is what we will endeavor to do today.

These pillars, of course, are Masonic representations of those pillars that were erected in the building of King Solomon’s temple. Scripture outlines the details of the temple, including the pillars, in great detail.

These descriptions are included in both the book of Kings and Chronicles. 1 Kings, Chapter 7, Verses 15-22 tell us:

15 - For he cast two pillars of brass, of eighteen cubits high apiece: and a line of twelve cubits did compass either of them about.

16 - And he made two chapiters of molten brass, to set upon the tops of the pillars: the height of the one chapiter was five cubits, and the height of the other chapiter was five cubits:

17 - And nets of checker work, and wreaths of chain work, for the chapiters which were upon the top of the pillars; seven for the one chapiter, and seven for the other chapiter.

18 - And he made the pillars, and two rows round about upon the one network, to cover the chapiters that were upon the top, with pomegranates: and so did he for the other chapiter.

19 - And the chapiters that were upon the top of the pillars were of lily work in the porch, four cubits.

20 - And the chapiters upon the two pillars had pomegranates also above, over against the belly which was by the network: and the pomegranates were two hundred in rows round about upon the other chapiter.

21 - And he set up the pillars in the porch of the temple: and he set up the right pillar, and called the name thereof Jachin: and he set up the left pillar, and called the name thereof Boaz.

22 - And upon the top of the pillars was lily work: so was the work of the pillars finished.

Most scholars hold that the pillars were not actually made of brass, as the process of making that alloy involves combining copper and zinc, which was unknown at this stage of history. Many contemporary sources that reference brass then are interpreted to mean copper or, more likely, bronze. I am told by W:. Bro. Palmer that the pillars here in this lodge (Hiram #7, Franklin, TN) were carefully measured when they were made so that they would preserve the scale outlined in scripture and reflected in ritual.

2 Chronicles, Chapter 3 echoes much of this description, but states that “Also he made before the house two pillars of thirty and five cubits high, and the chapiter that was on the top of each of them was five cubits.” There are essentially two explanations for the differing heights in the two books. One suggests that the overall height of each pillar was thirty-five cubits (18 cubits for the pillar itself, 5 for the chapiter, 4 for the lily-work, and an additional 8 for a base upon which the pillar was erected). The more commonly accepted rationalization is that, since 1 Kings indicates that the chapiter of each pillar covered one half cubit of the pillar’s body, 17 ½ cubits of each pillar was visible. With both pillars taken together, their total visible height, not including the chapiters, is thirty-five cubits.

Whether these pillars were smooth or fluted is unknown, and they are commonly depicted in both ways. In either case, both Kings and Chronicles place these pillars on the porch of the temple, and therefore they are typically displayed as being free-standing, rather than supporting any portion of the building itself. Therefore, in order to enter the temple, one must of necessity pass between them, and I believe that it is this moment that we specifically refer to when we say that we are “passed” to the degree of Fellowcraft. For this is the moment when we pass from the profane world without and into the holy ground of the temple itself.

This notion of passing between two pillars into some holy space or higher realm is a common thread throughout antiquity. This is particularly evident with respect to the Pillars of Hercules, which stand on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar. On the north side is the Rock of Gibraltar, and its southern counterpart is either Monte Hacho or Jebel Musa (Mount Moses). Plato recorded the location of Atlantis as being beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Renaissance depictions of the Pillars of Hercules sometimes include the phrase “ne plus ultra,” indicating that nothing lies further beyond those gates. This phrase also can be interpreted to indicate the state of perfection that has on some occasions been applied to the craft of Freemasonry itself, more specifically to the perfect ashlar.

But while these naturally occurring “pillars” were interpreted as having a more symbolic, spiritual application, men have been erecting dual pillars in their sacred spaces since the dawn of history. The temple site known as Gobekli Tepe lies in southern Turkey, near the Syrian border. This hilltop site is the oldest man-made religious structure ever discovered, dating to about 9,000 BC (that’s almost 7,000 years before the pyramids and Stonehenge). The ruins at this site clearly show that the temples there were circular structures, with two large free-standing pillars. These pillars are each capped by a rectangular block, which readily calls to mind the capitals described in the Solomonic pillars. They are also carved to take on certain human aspects, commonly believed to be the depiction of temple priests, who are wearing what appears to be loin cloths or aprons.

The Phoenicians placed their westernmost temple to one of their deities, Melqart (who is analogous to the Greek Hercules) just beyond the pillars in Cadiz. Their temples to Melqart, as with other deities that they worshiped, including Baal, Astarte, and Adon, all similarly were adorned with matching pillars located on either side of the entrance. In fact, it has been suggested that one of the primary reasons why King Solomon sought assistance from Hiram, King of Tyre and his master architect was due to the grandeur of the Tyrian temple to Baal. It is easy to see then how this notion of the pillars marking the entrance to a holy place was carried over from the Phoenicians to Solomon’s temple.

But Solomon was erecting a temple to Yahweh, not to Baal or Astarte. And though the physical elements were virtually identical, they must of necessity hearken back to the Hebrew nation and their God. Mackey says:

It has been supposed that Solomon, in erecting these pillars, had reference to the pillar of cloud and the pillar of fire which went before the Israelites in the wilderness, and that the right hand or South pillar represented the pillar of cloud, and the left hand or North pillar represented that of fire. Solomon did not simply erect them as ornaments to the Temple, but as memorials of God’s repeated promises of support to his people of Israel.

This excerpt is included in the explanatory lecture of the second degree in some jurisdictions, though not in Tennessee. It refers to Exodus Chapter 13, verse 21, which states, “By day the Lord went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud to guide them on their way and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, so that they could travel by day or night,” after setting out from Succoth (which incidentally is also the name of one of the locations where the temple pillars were cast).

These pillars may also have had reference to the two antediluvian pillars of Enoch. In fact, the first Masonic mention of pillars is found in the Cooke Manuscript, dated circa 1410. Enoch, who was the great-grandfather of Noah, was close to God, and according to Jewish tradition, learned much important knowledge from God, including the arts and sciences and the laws of the universe. In order to preserve this knowledge, he and his sons (Methuselah, Elisha and Elimelech) erected two pillars, one of stone, and a hollow one cast in brass, and upon those pillars Enoch engraved his wisdom. These materials were chosen to protect this important knowledge against any future destruction by either “conflagration or inundation,” as the stone pillar would survive a fire, while the hollow brass pillar would survive a flood. Evidence of this connection with the temple pillars, from a Masonic perspective, is still evident in our description of them, which includes a reference to their serving as vessels to preserve the archives of Masonry and to withstand “inundation and conflagration,” despite the fact that conflagration would easily destroy two brazen pillars. And here again, we see that these pillars make reference to both fire and water/cloud, as they did in our prior historical application concerning the Exodus.

This recurring association of the two pillars with the opposing forces of water and fire lead us naturally to the most obvious of the symbolic expressions of these furnishings—that of duality. If we accept the association with the pillars of Exodus, one pillar becomes associated with water, and the other with fire—two equal, but opposing forces. The ancient symbol for water was a downward pointing triangle, while that of fire was the same triangle pointed upward. This clearly illustrates the opposing nature of these two columns, and is suggestive of one of the key spiritual concepts that is omnipresent throughout Freemasonry: “As above, so below.” This same concept is repeated with equal force by the Masonic addition of the terrestrial and celestial spheres: “On earth as it is in Heaven.” This also suggests the most tangible of all dualisms—the masculine and the feminine. The left pillar is named Boaz, which translates roughly to “in strength” and is clearly an active, masculine concept. The right pillar, Jachin, translates to “God will establish,” is a more passive, creative notion, and can be directly associated with wisdom, or “Sophia,” which is feminine.

Dualism is an essential concept in virtually every system of religious or spiritual thought known to man. Whether this is expressed as creation vs. destruction; mind vs. body; or yin vs. yang, the notion of equal but opposing forces is omnipresent. Some depictions of the Solomonic pillars further reflect their oppositional nature by making one pillar in black and the other in white. This is NOT to be interpreted as equating to the notion of good vs. evil, for neither of these equal but opposite forces is inherently “better” than the other. We are told in scripture that there is a time to be born and a time to die, etc. illustrating that neither of the opposites is to be considered evil. Albert Pike further illuminates this distinction by stating that evil is not the opposite of good, but rather the absence of it, just as ignorance is the absence of wisdom and darkness is the absence of light. These dualistic forces that are symbolized by the two opposing pillars teach the concept of the necessary union of opposing forces, an idea which Bro. Ryan Driber names the “equilibrium of the contraries” in his paper of that name (Tennessee Lodge of Research 2005 Proceedings).

But a Masonic lodge is supported not only by the columns of Wisdom and Strength, but by that of Beauty as well. While these three columns are clearly delineated by the three stationed officers, they are also reflected at one particular moment, when the candidate passes between the two pillars. At that time, there are in fact three pillars: the two we have been discussing and the third represented by the candidate himself. As he passes between them, he represents the harmony, or balance between the two opposing forces, between the Senior Warden’s column of Strength and the Worshipful Master’s column of Wisdom. He becomes the pillar of Beauty—the embodiment of the Junior Warden. Just as the union of the downward pointing triangle of water and the upward pointing triangle of fire yield the six-pointed star of Israel, so does the union of King Solomon and Hiram, King of Tyre yield the synthesis which is Grand Master Hiram Abif, whose deceased father was a Tyrian and whose mother was a “widow of the tribe of Naphtali.”

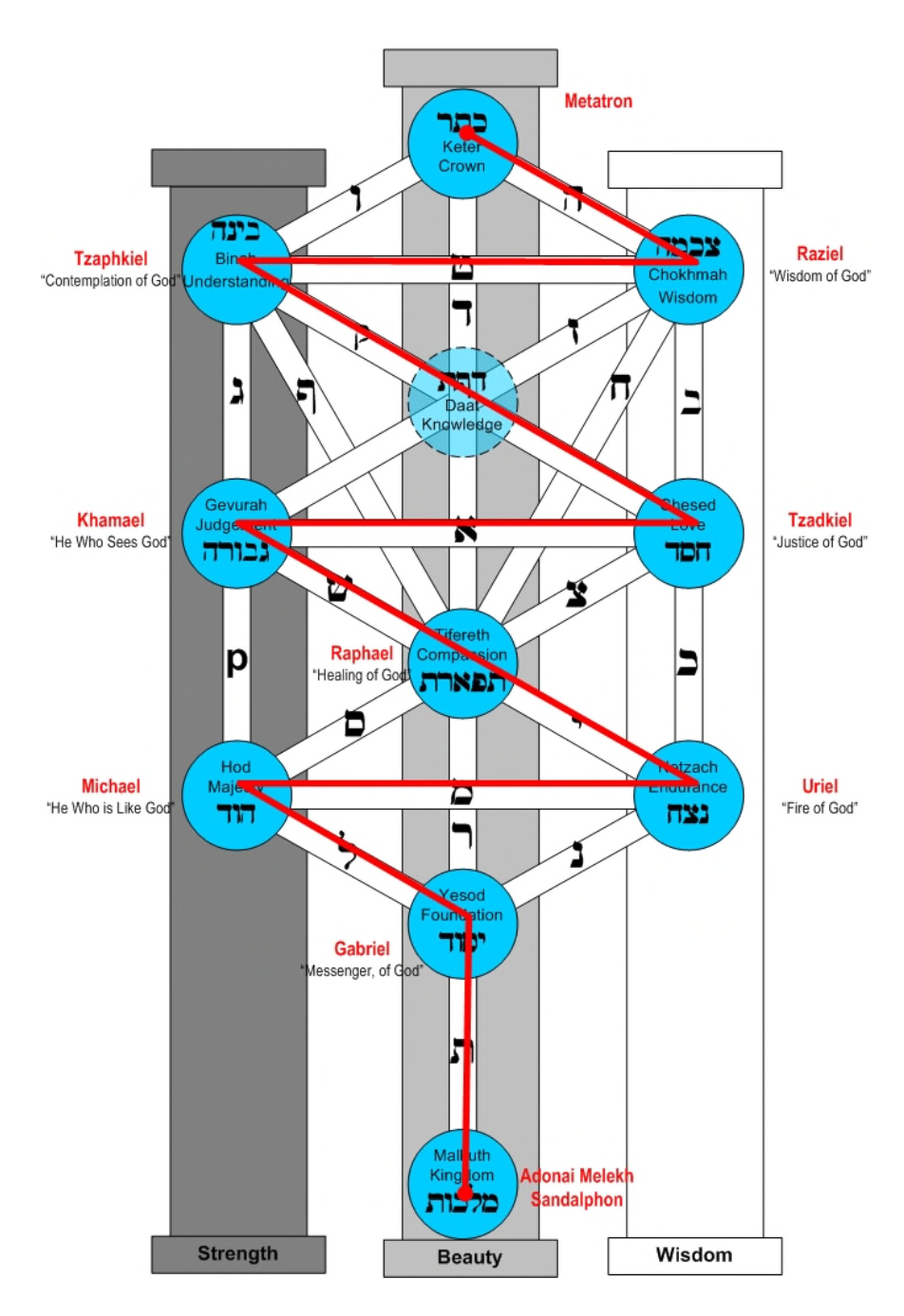

Much of the history and symbolism of Freemasonry comes from the Jewish tradition, and often more specifically from the Jewish mystical tradition known as Kabbalah. This school of thought teaches that God created the universe in ten utterances, each of which represents a specific attribute or emanation of the Deity. These emanations or sephiroth collectively form what is commonly called the Tree of Life, and are organized according to the three pillars of Wisdom, Strength and Beauty. The organization of these pillars exactly matches the placement of the two brazen pillars—Strength (Boaz) on the left, Wisdom (Jachin) on the right, and Beauty—often referred to as the Middle Pillar, represented by the candidate.

The base of this Middle Pillar is the sephirah (Hebrew for a single emanation of Deity, as opposed to the plural sephiroth) named Malkuth, which represents the material world or kingdom that is generated from the other manifestations of Deity. It is the beginning of the Kabbalist’s spiritual path toward enlightenment. The top of this Middle Pillar is the sephirah named Keter, which represents the crown or Godhead. In his journey toward the apex of this mountain of Truth, the seeker of light passes back and forth up a winding path between these pillars.

The goal of the student of this mystery school is to incline neither to the right, nor to the left, but to take from each pillar’s energy, always returning to balance himself in the harmony of the Middle Pillar. The temple cannot stand without the two supporting pillars, and if the initiate fails to build his spiritual temple without harmony between the two extremes, his temple cannot stand, and will suffer the same fate as that which fell to Samson’s might.

While the study of the Kabbalah is a deep and complex subject, even this cursory introduction shows a very clear parallel to the ascension of the candidate in the second degree. I do not claim to be an authority on the mysteries of the Kabbalah, or even on the symbols and meanings of Freemasonry. I do however believe Pike when he admonishes us to follow the streams of knowledge back to their “sources that well up in the remote past” where we will find the “origins and meaning of Masonry.” What I have offered today is one interpretation of the history and symbols of these two omnipresent pillars. It is my hope that in doing so, each of you may be moved to explore these mysteries further, and in turn arrive at your own understanding of their meaning to you. My only charge is that, when you do arrive at a knowledge of this, or any other symbol of Freemasonry, that you do not stop there and say, “I understand this.” Press onward, dig deeper, peel back yet another layer—for it is not the destination, but the journey through the pillars and up the winding staircase that yields the Mason his wages.